He was about 12 years old.

I had visited his class, carrying a large African tribal mask. After the teacher told the class that they were nobodies and were always going to be nobodies, she introduced me and left the room. It didn't matter if the teacher was African-American herself or not: the message was the same in all the classes I visited.

I told the kids they came from a long and beautiful tradition, that they had a proud heritage to uphold. Some of them tried on the mask, and we talked about African art, culture, and spirituality, music and dance.

I was collecting African tribal art at the time. I began because I noticed that no galleries were featuring it, that my college education had ignored it, and that it seemed to be considered a primitive craft with no real value. In fact the masks, and sculptures, were strong and emphatic. They arose from a vibrant spiritual faith and were part of significant rituals. It was a culture where no child was ever an orphan, because all of the children were cared for by the tribe. It was a culture where the bodies of dancers moved to different rhythms, feet to one, shoulders to another, heads and hands to yet another. Try it: it's not easy.

Culture aside, the pieces struck me as alive and powerful, not "p r e t t y", as defined by western criteria, but emphatic, with a raw vitality.

It turns out that Dominique de Menil(1) was also collecting African art, albeit on a much grander scale. She asked me to write a program, to be taught in elementary and middle schools in Houston. I trained docents, and looked for volunteers. There were many, but all for the private schools. Troubled, I went to schools in an area known as Houston's murder center. I was warned about damaged cars and disruptive behavior.

I never had a problem, not a scratch on my car, not a difficult student. It turned out to be one of the highights of my life. Those children gave their love, unstintingly. No one had visited their school before; no one had ever suggested that they came from a cherished tradition.

Eventually, the deMenil collection was donated to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, in a new section devoted to African Art. During the ensuing years curators, not only at MOMA but at other institutions and galleries as well, debated whether the works were craft rather than art. They ignored the pieces themselves and worried about their own reputations; some were threatened, I suspect, by the raw power emanating from the works.

The young man had a gift for drawing, so I encouraged him to enter his work in a city-wide competition for student art. He won an award. This was Houston in the 1970's, however, unable to acknowledge his talent. The award ceremony was held, but he was not invited. After a considerable ruckus, they agreed to send him his award certificate, too late to attend the ceremony.

He was only 12, and I was just beginning to understand uncivil rights and the depths of bigotry. I wish I could remember his name. But I will never forget the gift of love he gave me.

c. Corinne Whitaker 2020

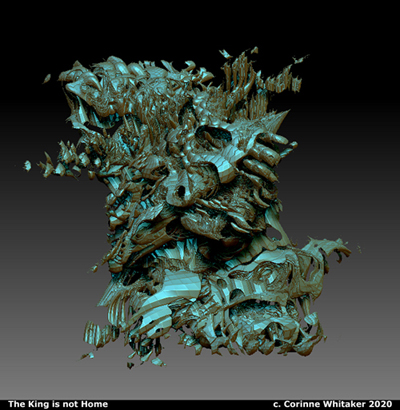

Looking at this sculptural form I recently created, there is little doubt about what influenced me, albeit unconsciously.

(1) de Menil

(2) The mask shown above was not part of my collection, although it is similar. You can find out about it here: senufo. My own collection was donated to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

front page , new paintings, new blobs, new sculpture, painting archives, blob archives, sculpture archives, photography archives, Archiblob archives, image of the month, blob of the month, art headlines, technology news, electronic quill, electronic quill archives, art smart quiz, world art news, eMusings, eMusings archive, readers feast, whitaker on the web, nations one, nations two, nations three, nations four, nations five, meet the giraffe, studio map, just desserts, Site of the Month, young at art,

want to know more about the art?

about the artist?